If Democracy is Broken, Middle Schoolers Can Fix It

by Justin Tosco, Peaceful Schools Facilitator

The current state of the world feels heavy. I can’t tell if things truly are worse than ever or if, when we zoom out, history will show this as just a blip on the arc of progress. What I do know is that right now, democracy feels fragile. I wrestle with the balance between moral clarity (naming dehumanization, condemning ideologies that harm the vulnerable) and strategic power-building (coalitions, persuasion, political wins).

I’m learning from others on this, but one place I return to often is the classroom. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, classrooms are microcosms of the society we have, and Montessori classrooms, in particular, have the privilege (and responsibility!) of being microcosms of the kind of societies we want. One example from my work as a middle school administrator in 2020 has stayed with me.

That fall, students were returning to school in the thick of the COVID debates. The political fervor around COVID was still very much raging. Were we endangering kids by reopening? Or ruining their education by keeping them home too long? Middle schoolers were tuned into these questions, and the conflict immediately bled into our school culture.

Two students in particular became lightning rods: one fiercely opposed to masks, another just as passionate about mandates. Their debates spilled from class to hallways, eventually spiraling into mini “campaigns” with coalitions of peers. It came to a head when I walked into school one morning to find every locker plastered with flyers - flyers that not only promoted masking for safety, they specifically named the other student and called him an anti-science idiot.

By the book, I should have launched an investigation that likely would have led to suspended students. Instead, I invited both students to a restorative circle - something I’d been trained in by Peaceful Schools North Carolina. Receiving training from the incredible faculty at Peaceful Schools prepared me to approach this challenge not only with care, but with the tools and skills that would ultimately lead to a positive outcome. What emerged not only shifted our school culture but also offers a model I wish more adults would embrace today.

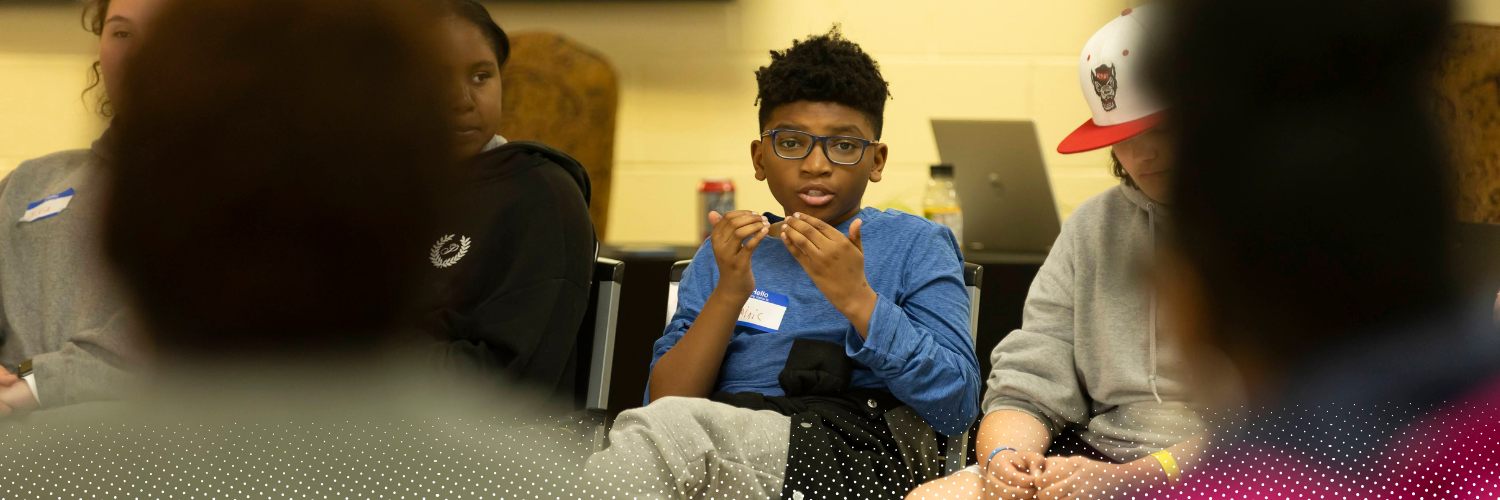

After thoughtful, respectful dialogue, both students shared that they felt they didn’t have opportunities in school to debate hot-button issues that mattered to them. Without that, their energy turned toxic. So together, we created a student-led discussion group. I worked with the teachers to carve out a time each week to fit it into our busy schedule. The students drafted ground rules, worked to recruit peers, and, most importantly, committed to co-leading, even though they couldn’t have been further apart politically.

Five years later, that discussion group called “Common Grownds” (the first student to make a poster realized her misspelling too late, so we ran with it - the goal is to “Grow” in Common Grownds) continues to meet weekly and be facilitated by students. Each year, two students take on leadership. Their responsibilities:

• Select topics based on peer interest

• Share FAQs and context ahead of discussions

• Facilitate conversations with classmates

• Teach respectful engagement with difficult ideas

Topics range from mass shootings to AI to affirmative action. Don’t get it twisted - these are not kumbaya circles. Discussions can get heated, feelings can be hurt, lines might get crossed. But the students come back the next week and try again. They try to ensure all voices are heard and try to amplify the voices that aren’t. They try to ask the right questions. They try to find truth. It’s often frustrating and uncomfortable but they keep trying because they are invested in each other, in their school, and the world.

More recently, I came across a New York Times article arguing that many of today’s social and political crises trace back to a simple problem: schools stopped teaching students how to communicate. For centuries, rhetoric (the art of speaking and listening) was central to education. In the modern era, it’s been pushed aside in favor of reading, math, and technical skills. Yet trust, conflict resolution, and group decision-making are essential for citizenship in an increasingly fractured world. And those are exactly the skills my students practice every week in Common Grownds.

At Peaceful Schools, we believe peace isn’t the absence of conflict, it’s the practice of engaging with empathy, curiosity, and courage. What I witnessed in this restorative circle, and what those students continue to practice in Common Grownds, embodies that spirit. When young people are taught to listen deeply, to disagree without dehumanizing, and to repair harm, they don’t just build stronger schools, they build the foundation of a more peaceful world.

I’ve often wished I could record these student discussions as a playbook for our politicians. Since I can’t, I’ll point you to a recent episode of the Ezra Klein podcast with Ta-Nehisi Coates. Their exchange is a good example of wrestling with disagreement without losing sight of humanity.

The TLDR is captured in these two quotes:

Klein: “If we keep losing power, the people we care about get hurt; we must rethink how to win and broaden who feels welcome.”

Coates: “If we blur the truth about hate to build coalitions, the people we care about get hurt; we must hold the line on human dignity.”

Yes and yes.